Return to Rousseau

I would even go so far as to say that we should return to the French revolutionaries in some things, even over against the Marxist tradition.

- Slavoj Žižek

When I was new to the left, anti-authoritarian ideas seemed to enjoy a lot of traction. The people I knew were situationists, anarcho-syndicalists, or council communists. They read Debord, Kropotkin, and Pannekoek. The Spanish Revolution was praised as a historical role model, “really existing socialism” on the other hand was dismissed as tyrannical and evil. The neoliberal capitalism of Western industrial nations was criticised not for its “laissez-faire” attitude as is fashionable today, but for being statist and authoritarian.

Such “ultra-left” ideas often led to an overemphasis on horizontality and direct action, which had particularly detrimental effects for those who wanted to get things done. Any kind of delegated authority was rejected, which meant that a functional division of labour within political groups was out of the question. Every minute detail had to be discussed collectively. Decisions could only be made as a group, and often nothing short of consensus would suffice. Horizontal structures don’t scale well, so organisations couldn’t get larger than a certain size.

The strict anti-authoritarianism of the ultra-left thus made it impossible to build powerful organisations, to act strategically, to be effective. These deficiencies were pointedly criticised by Srnicek and Williams in their Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics.

Somewhere during the later 2010s, leftists began to notice. They wanted to be politically active, to be effective. So they abandoned the dogmatic anti-authoritarianism of the ultra-left. Today's radical youth is no longer anarchist or situationist. It is instead oriented towards the state, espousing either social democracy or some form of Stalinism (“Marxism-Leninism”).

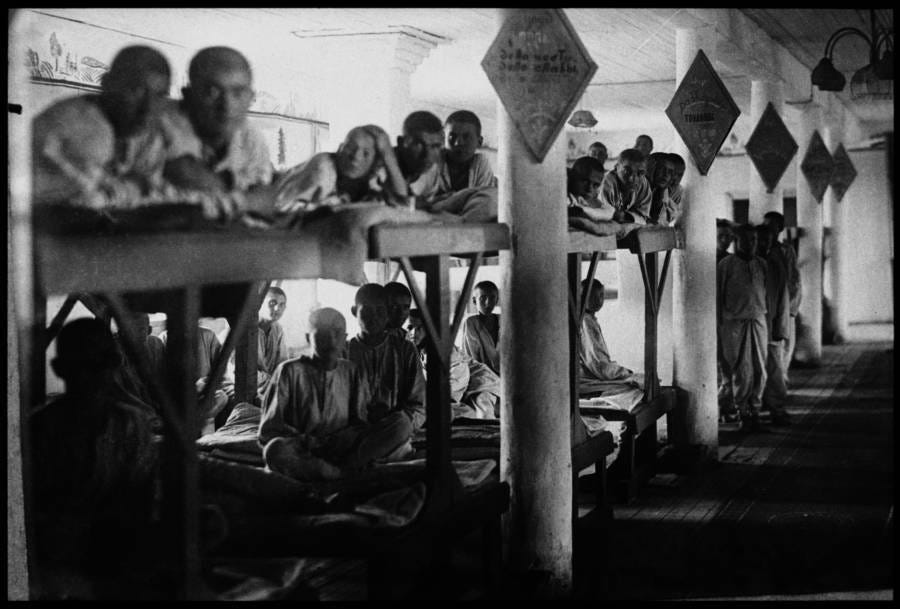

Oftentimes, people start out as what can best be described as woke social democrats. Once they radicalise, however, they become more and more sympathetic if not to Stalin and Mao, then at least to a form of Leninism which re-interprets the symptoms of the Bolshevik’s defeat – single party rule – as sound strategy. While ultra-leftist ideas might be ineffectual, authoritarian statism has historically led to the emergence of the most bloody excesses of tyrannical violence, which has discredited communism for many generations.

Those who celebrate state power and believe that the good can be enforced authoritatively make two basic assumptions:

1) We cannot trust that the correct opinion can be sustained within civil society.

2) We can trust that the right opinion can be sustained within the state apparatus.

Taken together, these assumptions are simply implausible. If we deem reason to be unable to hold its ground in civil society, why should it have a chance in the state apparatus? Why should it have an advantage where the greed for power prevails, where there is cronyism instead of rational debate, where membership in rackets trumps adherence to ideas? In civil society, truth and falsity are discursively determined by countless materially independent public intellectuals and citizens. In the state, by contrast, they are negotiated by corrupt bureaucrats on the basis of practical interest and in terms of future career opportunities.

The claim that truth has better chances in the state apparatus than on the street is obviously deluded. Does this mean that we should return to the ideas of the ultra-left? But we all know that rejecting the state in its entirety means abandoning any hope for real political success. A society without laws, without structure cannot exist. Reciprocity and mutual aid will never suffice to coordinate a complex modern economy, and political conflicts will not cease to exist after the end of capitalism. Unmediated cooperation is impossible, as is formless politics. Public institutions will be necessary, even in a post-capitalist society. So maybe we should take another look at authoritarian statism …

The left perpetually oscillates between those two poles. Either “pragmatic” authoritarianism or the dream of society as a hippie commune. Either the full affirmation of the state apparatus or the abolition of all political structures. Both poles are obviously wrong, and that is why they exist; the proponents of either must only unmask the deficiencies of the other to make their case.

While authoritarian socialism and anarchism seem to be polar opposites, they have something in common. Both underestimate the importance of political form. For authoritarians, form doesn’t matter; what matters is only content. If those who rule have the correct goals, that is if they support the struggle of the proletariat, then that’s that. Nothing else is necessary. For anarchists, form is simply rejected. Politics ceases to exist, or else, it must be a formless process.

The theoretical mistake that creates the false dichotomy between ultra-leftism and authoritarianism is the leftist inability to theorise structured political systems which are at the same time democratic. Being unable to imagine a society that is ordered, having laws, courts, and political institutions, but which is dominated neither by a single party nor a powerful state apparatus, they have to decide: abandon the state altogether, or fully embrace despotism as the only way to socialism.

Can we reject this premise? If yes, how can we have laws which do not benefit a small elite of capitalists or party cadres? How can we have government which is not tyrannical? How can large political structures survive without degenerating into chaos or dictatorship?

Neither Marxism nor the Anarchist tradition have answers here. We have to look somewhere else. 17th and 18th century political philosophers such as Algernon Sidney, Thomas Paine, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau were obsessed with the creation of constitutional arrangements that preserve freedom while guaranteeing order. Rousseau, for example, combined a commitment to direct democracy with an insistence on the rule of law, thereby laying the groundwork for a true people’s republic. Ideas such as these can help us navigate the problems of political form, and thereby escape the deadlock between authoritarian socialism and total state abolition.

The ideas created by those Enlightenment republicans were historically successful, inspiring the American and French revolutions and thereby aiding the birth of the bourgeois-democratic world order. Marx describes this order as a new step in the evolution of freedom, the most advanced stage of history witnessed so far, and the last station before communism. For all its faults and crimes, there has never been a more humane and free civilisation than the bourgeois-liberal one.

Leftists tend to view the political thought of the Enlightenment as a relic of the past. However it has much to teach to us. Yes, it needs to be complemented by the insights of Marxism; but at the same time, Marxism cannot survive without an infusion of Enlightenment political thought.

If we cannot build a truly democratic republic, we cannot build a socialist economy. At the same time, such a republic will never survive without socialism; it will be corrupted by the class interests of the bourgeoisie and the imperatives of capital. In order to complete the unfinished work of the Enlightenment, we must understand Marx. But we must also … return to Rousseau.